This article appeared in Knife Magazine in January 2023.

Know Your Knife Laws – The Tool That Would Not Be Killed

By Daniel C. Lawson, Attorney and Knife Expert

On April 4, 1956, the Governor of Pennsylvania signed two bills into law. The first of the two in the sequence created an entirely new section of the penal statutes captioned “Selling or Dispensing Knives, etc., Commonly Called “Switch-Blades.” This new section made it a misdemeanor to sell, dispense, give, deliver, or offer for sale any automatic knife.

The text of the second new law appears in the illustration and amended an existing section of the penal laws. The amendment added the wording: “or any knife, razor or cutting instrument, the blade of which can be exposed in an automatic way by switch, push-button, spring mechanism, or otherwise, to the existing list of ‘deadly weapons’ including any slungshot, handy-billy, and dirk-knife that could not lawfully be carried concealed.” Section two of the act provided it “shall take effect immediately.” PA-1955 Act

The efforts of John Sullivan, past president of the American Knife & Tool Institute (AKTI) and Director of Compliance at W.R. Case & Sons Cutlery Company, have resulted in a repeal of the above restrictions. Sullivan engaged other knifemakers in northwest Pennsylvania, including Guardian Tactical and Great Eastern Cutlery, along with Peters Heat Treating, Inc., to support the measure, guided by AKTI’s advocacy group Tremont Strategies. The legislation was sponsored by Representative Martin Causer, whose district includes historic Bradford, Pennsylvania, the home of W. R. Case & Sons. On November 3, 2022, HB 1929 was signed by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf and will become effective on January 3, 2023. (It would seem more logical and in keeping with due process that citizens be afforded 60 days advance notice of new criminal sanctions rather than the opposite, as occurred in 1956.)

What was so unique about a knife blade exposed by a push-button that necessitated a blanket prohibition on commerce? Moreover, what compelling problem in the State of Pennsylvania or the Nation some 66 years ago justified the need for immediate effect? An answer to these questions will not be apparent from an examination of crime data for that period. The restrictions signed into law were part of an overreaction to a non-existent problem by more than 30 states which began in 1951 and had plateaued by 1959.

The consensus view is that the germ of the “switchblade” hysteria was an article in the November 1950 issue of Women’s Home Companion1 written by Jack Harrison Pollack, a freelance writer who authored three books and over 500 magazine articles on various topics. A temporal connection between the article entitled “The Toy That Kills” and the onset of automatic knife restrictive legislation is discernible. The following year, Colorado enacted an automatic knife prohibition (HB 51 228), and various states followed.

Pollack’s article featured anecdotal accounts of fatalities involving “switchblades.” Names and dates might have enhanced the credibility of these accounts, but no such detail was provided. The piece was similarly lacking in empirical detail. The article ended with a desperate exhortation to the target audience – mothers – to “de-glamorize knife carrying” by their sons, to “work for passage of state laws,” and not wait lest those sons be ‘murdered with a toy pocketknife.’ In doing so, he sensationalized automatic knives.

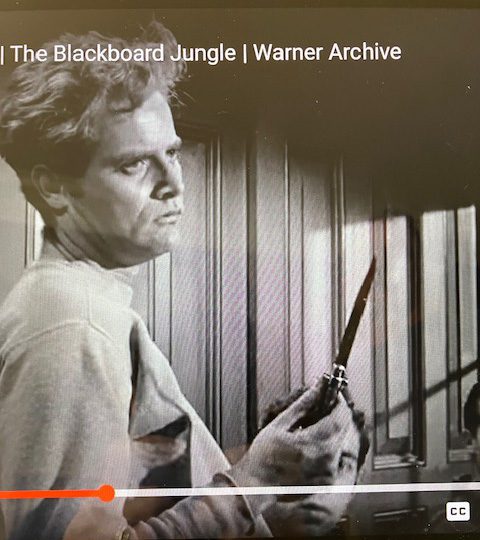

Hollywood thrives on sensationalism. Automatic knives were used to provide riveting visual and dramatic effects, susceptible to drama. The entertainment industry enthusiastically applied its creative talents to kindle, exaggerate, and exploit the “switchblade menace.” The prime example may be the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle, which presented a conflict in the classroom. It includes a scene where the antagonist Artie West, played by Vic Morrow, threatens – and wounds – the teacher with an oversized switchblade featuring what appears to be a six-inch, bayonet-grind “stiletto” blade.

Hollywood thrives on sensationalism. Automatic knives were used to provide riveting visual and dramatic effects, susceptible to drama. The entertainment industry enthusiastically applied its creative talents to kindle, exaggerate, and exploit the “switchblade menace.” The prime example may be the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle, which presented a conflict in the classroom. It includes a scene where the antagonist Artie West, played by Vic Morrow, threatens – and wounds – the teacher with an oversized switchblade featuring what appears to be a six-inch, bayonet-grind “stiletto” blade.

The disingenuous nature of the legislative response to a teenage fad is well illustrated by the example of New York State. In March 1954, New York enacted a prohibition on the sale and possession of

any knife which has a blade that opens automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring, or other device in the handle of the knife.

An exception to this prohibition was provided where such a knife was for use in connection with one’s business, trade, or profession. Thus, the knives could lawfully be sold and purchased by anyone who stated that it was appurtenant to earning his job. Another exception was created for those licensed to pursue hunting, fishing, or fur trapping.

Less than two years later, the New York legislature removed the “business, trade, or profession” exception to the possession prohibition. The reasoning, as reported in the New York State Legislative Annual for 1956, was enforcement difficulties arising from the trade/profession exception, which had a “vitiating” effect on the statute, and that the knives had no “legitimate and necessary purpose.” The report does not suggest automatic knife violence or criminal use was a problem. Instead, prosecutions for possession were being spoiled – a more basic word for “vitiate” – by the trade/profession exception.

Essentially, the 1954 New York restrictions were determined to be of little practical effect. Yet, in 1958 proponents of the Federal Switchblade Act cited the ineffectiveness of the 1954 state act as support for federal intervention notwithstanding the 1956 revision:

IN NEW YORK CITY ALONE IN 1956, THERE WAS AN INCREASE OF 92.1 PERCENT OF THOSE UNDER 16 ARRESTED FOR THE POSSESSION OF DANGEROUS WEAPONS, ONE OF THE MOST COMMON OF WHICH IS THE SWITCHBLADE KNIFE. S. Rep. No. 1980, 85TH Cong (All capitals in the original.)

The 92.1 % increase occurred while the 1954 version, with exemptions, was in effect. It may appear to be significant until we pause to reflect that it simply shows an increase in the rate of arrests, under the age of 16, for possession after an increase in the universe of prohibited items. It is in no way indicative of criminal usage of the subject knives. In other words, while the knives were available for sale based on the toothless 1954 restriction – and during a period when “switchblade” possession was incentivized by popular culture – more youths were found to be in possession of the same. If the burgeoning number of switchblades were being used to commit or threaten violence, one would expect it to be reflected by empirical data.

Another remarkable aspect of the 1956 New York version was that, while it was supposedly justified by the fact that “switchblade” knives had no legitimate or necessary purpose, New York law provides a very broad range of exceptions for public sector employees as well as hunters, fishers, and trappers. (See the New State Knife Laws precis on the AKTI website and “Exceptionality,” article which appears in the October 2022 edition of Knife Magazine.)

New York officials became unsatisfied with the 1956 version of its “switchblade” restriction. The issue was the mislabeled “gravity knife,” which became a substitute for the switchblade.

The case of United States v Irizarry 509 F.Supp.2d 198 (2007) recites the history behind the March 1958 “gravity knife” law in New York:

The gravity knife, seen as the “new tool for teenage crime,” was cheap and accessible all across the city and, according to Ralph Whelan, the executive director of the Youth Board, was used in “many of the most vicious crimes by young people.” Id. New York Supreme Court Justice John E. Cone, chairman of the Committee to Ban Teenage Weapons, reported that youth taunted police officers across the city with the gravity knife, knowing that the law did not condemn their conduct.

The response to officers being taunted was a gravity knife prohibition. It became the basis for the prosecution of thousands of untold persons where officers, ironically, could open a folding knife using the wrist flick test developed by the Manhattan district attorney’s office. That test was eventually declared unconstitutional in Cracco v. Vance, 376 F.Supp.3d 304 (2019).

The federal government enacted restrictions on interstate commerce in automatic knives in October 1958, which also prohibited the importation of the “stiletto” styled knives from Maniago, Italy. Some legislative “piling on” occurred in a few states the following year. The end of the 1950s decade brought a practical end to new automatic knife restrictions. A small minority of the states had avoided the stampede, but the supply was severely tightened.

The widespread belief that automatic knives represented some profound public menace persisted. In December of 1984, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled in the case of State v Delgado, 692 P2d. 610 that the automatic knife prohibition enacted in 1957 was inconsistent with the Oregon Constitution. The Oregon legislature reflexively enacted a concealed carry restriction in 1985 under the principle that it had the constitutional authority to regulate the manner of carry. The legislature evidently made no effort to ascertain whether a basis for the carry restriction existed.

The demand for a handy tool preexisted and continued (despite the suspension of critical thinking) regarding one-hand operable knives that prevailed beginning in the 1950s. Knife users across the country wanted the safety and convenience of one-hand operability. Knifemakers developed features such as thumb studs and declivities, which were purely manual, and then hybrid designs that we often refer to as “assisted openers.”

Prosecutors sometimes viewed these innovations as unlawful. Through the efforts of C.J. Buck and Les de Asis, the knife industry pioneered the “bias toward closure” standard, beginning in the State of California. This language became the basis of the 2009 Amendment to the Federal Switchblade Act. That amendment effectively diminished the distinction between automatic and manual knives to the point of being practically meaningless.

In 2010, Jennifer “Jenn” Coffey, an Emergency Medical Technician and elected representative in New Hampshire, prevailed upon her fellow legislators to repeal its “switchblade” prohibition. Her persuasive argument was the need for a one-hand operable emergency tool. New Hampshire did not devolve into chaos upon enacting the bill she sponsored. Beginning in 2012, other states similarly removed automatic knife prohibitions without any attendant fluctuation in knife crime statistics.

Pennsylvania is the 21st state to effectively reverse restrictions imposed during the hysteria of the 1950s, when HB 1929 was signed into law on November 3, 2022, as outlined above. Those restrictions had criminalized a product line of W.R Case and other knifemakers in Pennsylvania.

The automatic knife was never a toy for teens. Jack Pollack and others bestowed it with credential status and benefited from the sensation they curated. The knife community has prevailed. It refused to concede. The number of states with automatic knife commerce and carry prohibitions has now dwindled to four. A handful of states stubbornly cling to arbitrary and unwise restrictions. AKTI continues its efforts to eliminate all types of improvident restrictions on man’s oldest tool.

For reliable, updated knife law information, visit www.stateknifelaws.com, and for ways to support the work of the American Knife &Tool Institute, visit www.akti.org to join, renew, contribute, or bid on our monthly online knife auction.

________________________

1Women’s Home Companion was a monthly magazine published from 1873 to 1957.